(Impressions following my first viewing, August 2024:)

There’s always something to be said for the bottomless pit of cinematic inspiration that hinges on the awkwardness of the teen years – from the desire to fit in (or not); the alienation and isolation of high-school social castes; and the propensity to drift from friends without warning or explanation. Everyone has a different experience – or perhaps a more nuanced experience – as we grapple with the transitions of social, psychological, and physical change.

The pit is as inexorable as it is inexhaustible. Can you dig it?

Said transitions are explored in Jane Schoenbrun’s sophomore effort, I Saw the TV Glow.

The characters are vapid…bordering on lobotomized.

The emotions they express are unrelated to anything resembling human norms.

They are awkward and weird – bordering on cold and unsympathetic – throughout. (The film itself spans decades.)

Perhaps Schoenbrun is clinging too hard to David Lynch’s dreamlike aesthetic, and the execution rings too loudly with self-consciousness. There are monologues wherein characters use such (neon) purple metaphors to attempt to explain what they’re feeling, it almost comes off as unintentionally comedic.

There’s something too precious about the whole enterprise for me to completely embrace it, and said preciousness veers into pretension at times.

Yet…

There is something that resonates about all the deliberate awkwardness, weirdness, and coldness. For what are our formative years, if not awkward? Grappling with physiological changes is one thing, but figuring out the workings of a world that grows more complicated – unnecessarily so – as we age is something else altogether.

One parting senior at my high school listed this as his yearbook quote (paraphrase): “The challenge is preserving your individuality in a world where everybody wants you to be the same.”

And I get the preciousness; the emo-before-Emo angst of these disenfranchised characters whose home lives are unfavorable-to-unbearable. Wes Anderson – of whom Schoenbrun also seems to be an adherent – has mined an entire career out of privileged characters who can’t get a handle on their own neuroses.

The writer-director hews to a sense of the unexpected, introducing what seems like a rather mundane plot (two teens who form a bond over a TV show called “The Pink Opaque”), only to subject the viewer to subtle-to-aggressive shifts in character and storytelling as the oblique plot unfolds.

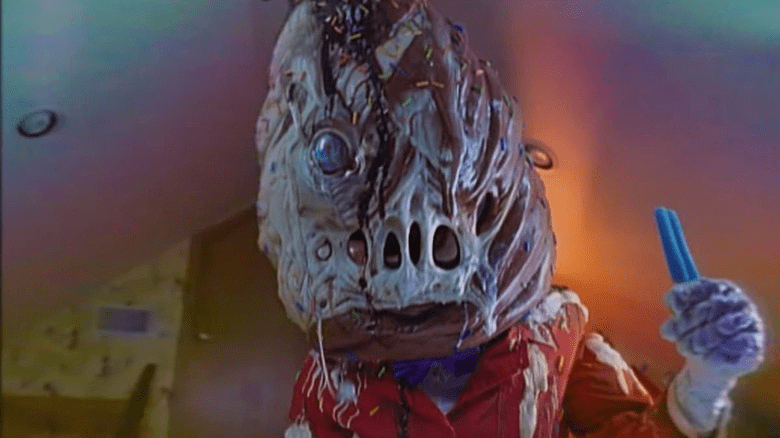

The whole experience exists in a realm of blacklights and bright, cotton-candy colors that are frequently buffeted by literal darkness (with many sequences occurring at night). Which makes sense for the subtle, horror-tinged fantasy elements (or vice versa) on display. As with We’re All Going to the World’s Fair, Schoenbrun does have an eye for halting imagery (a stop-motion ode to Melies’ Moon; a menacing ice-cream truck; a horrific anthropomorphic ice-cream cone) that makes a case for film being the correct medium for her art.

There’s a lot going on here, and I’m not sure it all works. The strongest thread may be that of the characters’ perceptions of fantasy and reality, but leaving enough metaphysical space in the narrative to not disavow one or the other, nor argue which realm the events of the film are occurring in. So, yes, delusion is another over-arcing theme here, with the filmmaker providing no definitive answers as to whose appraisal of the world is right or wrong. Loneliness is also strong among Schoenbrun’s list of recurring themes, and the aforementioned coldness of these characters makes even their moments of emotional interaction ring queasily hollow – but the more I think on it, the more I find this an interesting subversion of the overt (and often insincere and inauthentic) sentimentality present in most coming-of-age films. Fear – of others; of the unknown; of one’s true self – ties it all together, which is perhaps why Schoenbrun’s films have earned favor among the horror crowd.

“John Hughes for the rest of us” could easily be a poster blurb.

But there are moments that don’t feel necessary, and somewhat hinder the flow and half-asleep spell I Saw the TV Glow casts: the narration from protagonist Owen (Justice Smith) could have been reduced or eliminated, allowing the viewer to marinate in the narrative riddles and thematic paradoxes on display; similarly, I wasn’t a fan of the narration turning into moments where Owen breaks the Fourth Wall to fill in narrative gaps. Something about it messed with the strange emotional pulse of things and, at worst, felt pandering to modern audiences who can’t appreciate something unless there’s a reflexive irony at play.

I also wasn’t very smitten with a detour into a nightclub featuring two musical numbers where the performers explicitly drop plot details or themes (“psychic wound!” King Woman howls repeatedly) to make sure the viewer “gets” what’s going on. Again, something pandering and unnecessary about it, though the performers themselves are engaging.

And, in another bit of sledgehammer obviousness, there’s a character called “Mr. Melancholy.”

In its best moments, Schoenbrun presents the all-absorbing power of the cathode-ray tube as having the power to inform, distort, and…

(Impressions following my second viewing, November 2024:)

…expand the imagination. I was genuinely surprised when I Saw the TV Glow abandoned its LSD-laced take on a coming-of-age story to follow Owen through the subsequent decades of his life, culminating in an existence where fantasy and reality are clearly delineated, but the perception of reality is where the escapism of fantasy becomes an essential survival tool.

The washable neon paint on the suburban street says: there is still time.

Schoenbrun approaches the titular glow of the cathode ray tube as conducive to creature comfort, offering a vessel through which imagination can flourish. This piece of filmic art in particular proves that kids who were raised on cartoons and weird fantasy shows need not be regurgitators of their influences once they come of age and present their own art to the masses.

In a bit of opportune timing, within a week of watching I Saw the TV Glow, I went to a screening of David Cronenberg’s Videodrome at the Mahoning Drive-In. It was only while Max Renn (James Woods) was undergoing his own physiological transformation at the hands of a manipulative bootleg torture program that I had a “eureka” moment that put Schoenbrun’s creation into greater perspective.

Cronenberg has always treated human characters as a necessary evil in tales designed to push conceptual parameters of horror and science fiction; of seeing just how far the body – as a complex system of bones, organs, and blood – can be pushed before its humanity dissociates. Before it becomes the new flesh, if you will.

While Cronenberg’s filmography has detractors who take his clinical, often cold approach to human emotions to task, Schoenbrun – through a similar, surface-level coldness – finds the beating heart beneath the apprehension and uncertainty that accompanies the formation of identity during one of the most precarious periods in a human’s life cycle.

3.5 out of 5 stars

Leave a reply to blackcabprod Cancel reply