[Note: In order to preserve the mentality in which this piece was written, minimal editing has been done.]

“Words don’t do it justice.”

“There are no words.”

No, there are always words. When there’s nothing else, there are, as Hamlet famously said: “Words, words, words.”

It’s the weight of the words (worlds?) that make them feel less than significant; incapable of gathering meaning in a manner that’s robust and comprehensive enough.

This is something I’ve struggled with since I decided I had an interest in the written word.

The best writers can stir emotion and put the reader in theirs (or their fictional characters’) shoes, thus consummating a transference of feeling; of relatability.

Sometimes the act of writing is mentally taxing for this very reason; one cannot force or anticipate that transference, and the best words are often those that come to us with the greatest of ease.

Oftentimes, less thought = more powerful expression.

So when I peer into the dark, unknowable void beyond this earthly life, I tend to flounder with my chosen form of expression.

My feelings on a human afterlife are undecided. My mentality is one of hope that a) we can’t remember ourselves or our relationships, and we just sort of bump into one another for eternity; and b) that it’s not ruled over by the billionaire oligarchs who’ve made our daily life a living hell; a capitalist “contest” for survival; a dry run for The Purge or some other dystopia.

My feelings on a pet afterlife are as such: as someone who tears up every time I read “The Rainbow Bridge,” I want the pets I’ve known (whether mine or someone else’s) to exist in a reality free of pain, suffering, disease, and mortality; where every cat, dog, hamster, or axolotl never wants for anything, and can live on a plane of liberation – one that’s unencumbered by humans who want the animal, but not the responsibility.

My partner adopted Willow, a senior cat, in September 2023. The rescue estimated her to be 8 years old at the time.

She’d longed for a cat to call her own, since my Kima is infamous for loving only me and tolerating everybody else.

Later on, someone would refer to Willow as “a unicorn,” since her behavior set her apart from the stereotypes that accompany those of the feline persuasion.

A social being, Willow approached anybody new who walked through the door as a potential convert to the feline cause, commandeering laps for sleeping and palms for petting her burnished, shimmering, striped-walnut coat.

When me and my partner would be out of the house – even for a simple grocery run – Willow would always be waiting next to the door when we returned. While we were concerned she may get outside, this fortunately never happened.

Her curiosity and persistence exceeded even that of the most curious and persistent cats I’ve known throughout my life: upon adoption, she immediately made herself at home, much to Kima’s chagrin, exploring as many rooms as possible.

Willow loved to be carried around, over the shoulder; she could maintain this stance for untold minutes if the human arm was willing enough. One of the reasons my partner nicknamed her “Babygirl.”

Other nicknames included: “Willowbabe” (to be pronounced like the ticket taker pronounces the destination in that classic Twilight Zone episode, “A Stop at Willoughby”).

My partner coined “Bellybellybelly” and “Buddha-Belly” because of her rounded pear-shape and her willingness to allow humans to rub her belly without objection.

She always reminded me of the “rolling fatties” meme:

Whether standing or sitting, Willow would periodically peer up at me with her piercing green eyes and climb up my leg with the end goal of slumping over my shoulder or being cradled against my chest. This led to some particularly unproductive work-from-home days.

But, in thinking about this gesture and the extrasensory mythologizing that’s surrounded cats since their inception, perhaps Willow was tuning to a stressed or lonely wavelength, and sought to refocus my mind on something that brought relief and comfort – perhaps even forgetfulness – to that stressed state. Cats have a knack for bringing comfort, as much as they know how to stake claims at the most comfortable spots in a dwelling.

In front of nearly every upstairs vent in our house is a blanket for the express purpose of her to curl up in front of and let the heat blast out over her during the cold-weather months. There’s nothing as uniquely pleasing as listening to the audible, in-and-out “hmm” of a cat who’s utterly relaxed and at peace; in the midst of a sleep deeper than any human could hope for.

Willow would spend her mornings in a relaxed or restful state, and come to life in the afternoons, becoming restless on days when my partner was in the office, always anticipating her return. In the evenings, she would nestle on the couch with my partner, sometimes under a comfortable flannel blanket.

Like I said: cats prioritize comfort. We humans could learn much from them.

I remembered having reservations when my partner told me she’d filled out the adoption papers for Willow, having had years-ago situations of male cats who would spray around the house because of ego and hierarchical power struggles. And Kima had been an “only cat” for many years before Willow entered the picture.

So, most of our integration problems stemmed from our human foot-dragging about bad past experiences.

When we went on vacation in the UK last October, we believe a pervasive loneliness inspired the ever-determined, unflappable Willow to scale a baby gate we’d had installed at the kitchen/living-room threshold to keep them separated. The caregiver during this time noted that she would find Willow and Kima sleeping “together” in the basement whenever she’d come over to check on them.

While there was a sense of relief in how the integration issue had “resolved” itself, and Willow made herself welcome in my basement “man cave,” Kima never became cuddly with her. In fact, if Willow got a millimeter too close, Kima would crouch and hiss, to which the unflappable feline would stare for a moment before continuing to some unknown destination, unperturbed by the encounter.

Willow was persistent, though – I think she wanted to be friends with Kima, but the latter’s introversion proved insurmountable for her extroversion. I admired the effort and eventually became very hands-off with their interactions. As many told us: “they have to figure it out for themselves.”

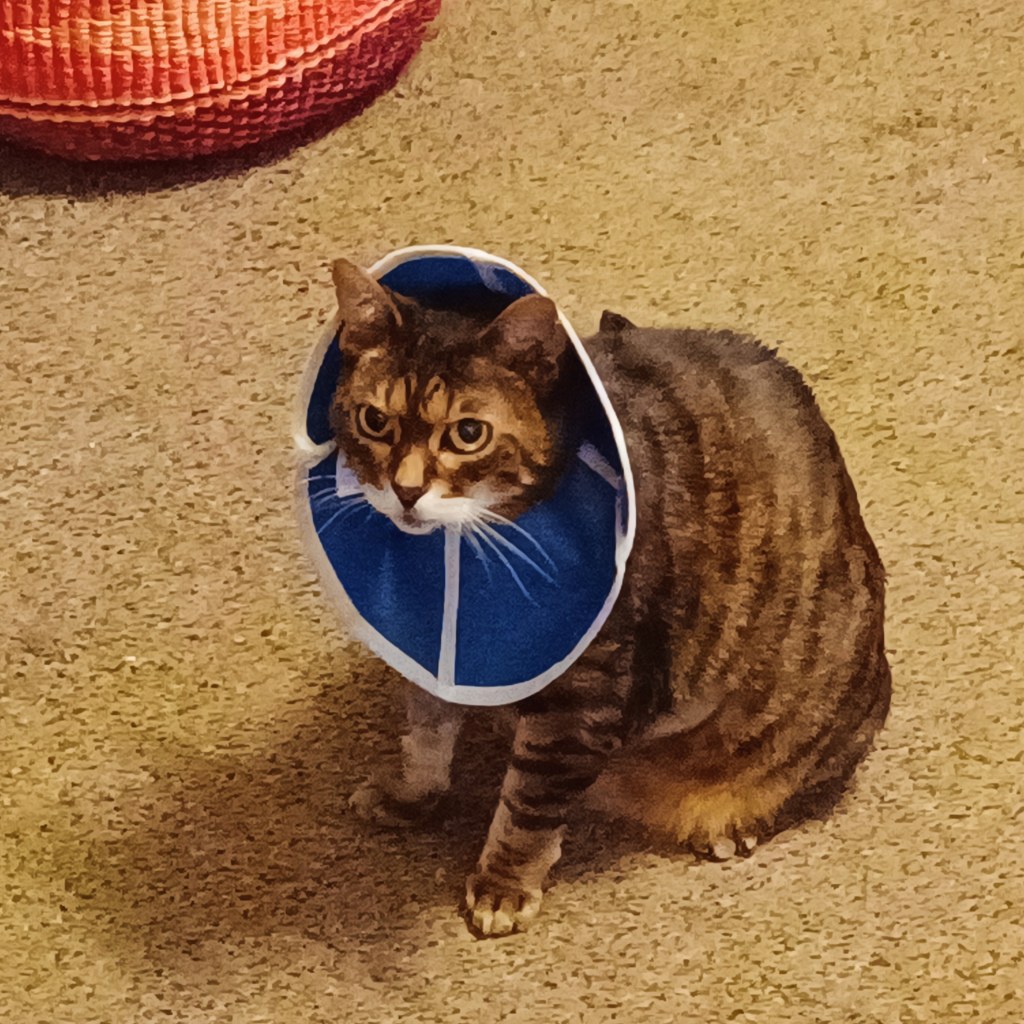

I admire her resiliency. She had a partial mastectomy due to a tumor and wore a “cone” for a week (maybe longer) to allow the incision area to heal. This reminded me of a time when my black cat “Missy” was apparently sideswiped by a car, had a tube placed in her back (I can’t remember why, I was in single digits at the time), and promptly ripped it out upon returning home. She ended up living 20 years.

Unfortunately, Willow found herself crouching and wheezing loudly in late 2024, to the point where my partner set up a vet appointment to have her checked out.

The prognosis was devastating: Willow had lung cancer, and in such a phase that euthanasia was recommended due to her quality of life.

And even though I’m drafting this on the eve of her final appointment (January 17 at 11am), I’m finding myself referring to her in the past tense, even though she is very much still here, dozing on a heat mat in front of a vent in my partner’s room on a bitterly cold day.

Since receiving this news on January 14, we’ve both been in a state of advance mourning, sharing tear-streaked breakdowns over Willow’s fate.

It’s bringing back my own memories of the cats I’ve had to say “goodbye” to over the years, particularly those who saw their lives cut short by physical condition. My dad and I fled the vet in Seven Valleys after dropping off our longtime companion Brownie because we were too cowardly to remain in the room for the procedure; then there was Grayman, whose ultimate malady eludes me (he had a bum leg, and once came in from an outdoor adventure with a glob on his crown that resembled a popped zit), but who went to rest surrounded by everyone in my family; and my beloved Weiss, whose otherwise healthy life was cut short by feline leukemia in 2018, leading to a head-spinning couple of hours at the emergency vet, and many tears shed as I listened to her hum her final purr as she drifted away.

No animal lover looks forward to this. When my partner asked me “why do we do this to ourselves?” I answered, “because of the immense joy they bring to our lives while they’re here.” And I stand by that. I don’t know how many cats I’ve interacted with in my life, but each leaves an impression, from those that live with us and nuzzle their way into our hearts over the course of many years, or strays who meow or rub against us in hope of getting sustenance or a chin-scratch.

It’s ironic that, as I type this, the news of filmmaker David Lynch’s passing (January 16) has hit the major news outlets and social media, with fans expressing their sadness at this immense loss to the arts (and the world, really). But something I really gravitated toward – especially in recent years – was Lynch’s embrace of the ambiguous; the enigmatic; the unanswerable. I remember an interview (around the time of Lost Highway in 1997) where he expressed his disappointment when a mystery was resolved, and cited the political and interpersonal chaos that caps Chinatown – with its iconic final line – as a case where the main mystery is “solved,” but the story and characters branch out into unknowable places that go unexplored, because that’s when the credits begin to roll.

Not unlike Lynch, cats are enigmatic creatures who, if we are fortunate enough to be chosen, find ourselves altering our behaviors and mentalities to embrace their personalities, and look in awe at their movements, sounds, and other forms of expression. Every nuance becomes significant; a cause to widen our eyes and smile and make our minds whirl in wonderment. As humans, we can infer what a “meow” or chirp from our favorite feline means, but there will always be a disconnect in the interspecies communication that makes the furry creatures consistently fascinating and mysteriously lovable, no matter how many we meet over the course of our lives.

Perhaps, like Lynch, cats are something outside of our world that just happen to live within it. Maybe they’re the fabled unicorns in disguise; the ones that have been in front of us for centuries. And Willow was certainly one of a kind, even within the heavily-populated landscape of unicorn-kitties.

We’ll love you always, Little Girl.

Leave a comment