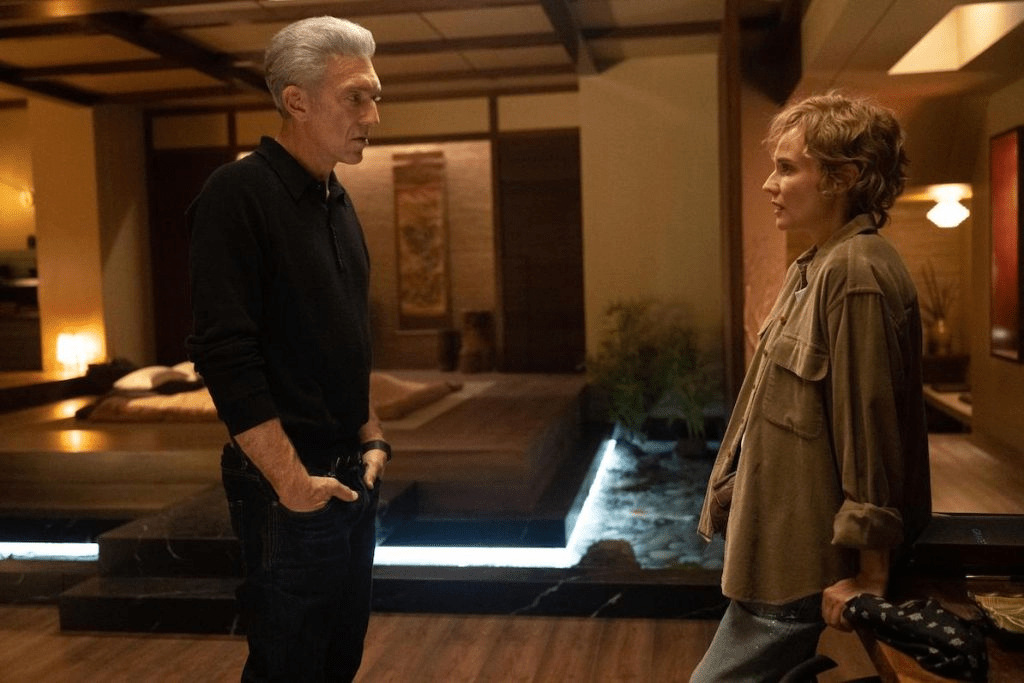

Melancholy reverberates throughout The Shrouds. It’s evident, first and foremost, in wealthy protagonist Karsh (Vincent Cassel, made up to look like writer-director David Cronenberg), who is so stricken by the loss of his wife, it inspires him to create an observational technology that allows the (wealthy) bereaved to monitor their loved ones as they disintegrate six feet below the surface.

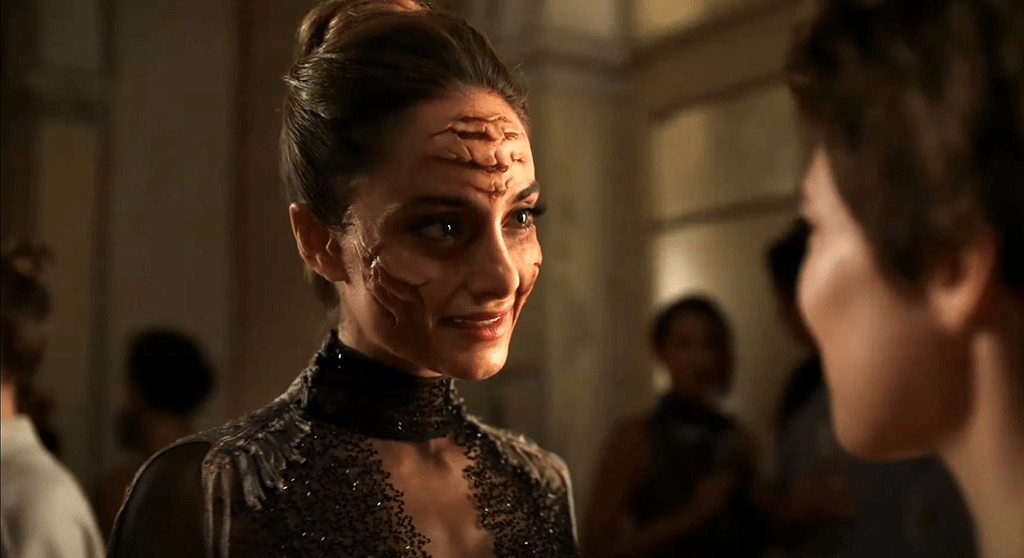

The subject is morbid – and morbidly funny – in Cronenberg’s capable hands, to the point where the film opens with Karsh gushing over the image of his decomposing wife, Becca (Diane Kruger), while his blind date awkwardly tries – and fails – to mask her bewilderment, revulsion, and horror.

Not unlike Eric Packer in Cosmopolis, Karsh has accumulated untold wealth through his innovations (controlled via an app called “GraveTech”), yet also seems blithely unaware of just what is going on within his company. One of the sources of dark humor and suspense in The Shrouds is the man’s persistent lack of awareness toward the people, events, and forces transpiring against him.

There is a narrative through-line of global conspiracy (with allusions to Russian and Chinese factions looking to manipulate GraveTech’s data and software for duplicitous means) that critics with a greater grasp on world history and current events could apply a more analytical lens to. But I feel like Cronenberg’s greater implications for Karsh and those within his immediate orbit have little to do with the company’s intentions of expanding its reach to grave sites in Budapest and Reykjavik. It’s more a MacGuffin – a narrative ping-pong ball the writer-director uses to “shroud” the narrative in additional political murkiness. (And, for what it’s worth, it works well.)

What’s interesting about The Shrouds is what’s interesting about Cronenberg at this late – perhaps final – stage of his cinematic evolution: Karsh is the viewer surrogate; a perpetual bystander to the inevitabilities of his creation (the plot catalyst is the vandalism of The Shrouds, and the subsequent data breach), he is always “in the dark” and missing information to make sense of the “how” and “why” and “who(m)” of the mystery surrounding him. As a result, Cronenberg gives the viewer just enough to hinge multiple hypotheses on, while leaving the ultimate outcome on a deliciously ambiguous and maddening note.

Karsh also represents another in a long line of protagonists whose fixation on technology and the limitations of human mortality leads him down a path of moral and physical entropy. Like Max Renn in Videodrome, Seth Brundle in The Fly, the car-accident cultists in Crash, or Eric Packer in Cosmopolis, Karsh spirals toward paranoia and self-destruction, but with The Shrouds, Cronenberg is less interested in literally turning bodies inside-out than he is curling up in the dark, perpetual unease lodged in the pit of one’s stomach.

This is one of the filmmaker’s more dialog-dense films, and is largely lacking in the FX-driven showiness of his decades-earlier works. At times, its scenes of two or three characters exchanging dialog feels particularly stagebound. Viewers of 2022’s Crimes of the Future will see an echo of the character intimacy here, and those who read his novel, Consumed, will notice the overly detailed mythos that still leave enough omitted to provoke speculation.

There are aesthetic pleasures to be had, such as the shadows and darkness that permeate most scenes, leaving only natural light (or the illusion thereof) to illuminate the characters. It’s a nice thematic touch that only adds to the literal association of dead bodies buried beneath the earth, and Karsh’s own status as a bystander left “in the dark” to what’s occurring around him. As Cronenberg’s casts have become more whittled down, so, too, has the feeling of defenselessness over the ability to change fate’s course – so why bother resisting?

Cronenberg even makes the suggestion that grief over the loss of a loved one – most of all a long-term partner – is the ideal time for ill-informed decisions to take on unforeseen consequences (even if said consequences happen years later). Mourning is a time of emotional contradiction and confusion, often compounded by the well-wishes of those that encircle the bereaved. Sometimes, those well-wishes are tinged with insincerity or ulterior motives.

The Shrouds also speaks to a certain repression of the flesh that the filmmaker has spent his career exploring and exploding – Karsh has towed a line with his wife’s sister, Terry (also Kruger); and her ex-husband (and Karsh’s right-hand tech savant), Maury (Guy Pearce). But as more questions pile up, the more uninhibited Karsh becomes, taking advantage of personal and professional trust in the name of the entitlement of primal orgasmic release. He’s haunted, riddled with guilt, and worn down by the moral and ethical controversies that hover over his creation, so there is something genuinely cathartic and shocking about a late-occurring sex scene, both in its explicitness and the near-incestual taboo its two characters engage in.

Through this, Cronenberg suggests that the propriety of a moral code is something mankind willingly shackles itself to – at the expense of pleasure; at the expense of closure; a mechanism to maintain self-flagellation in the name of cessation of desire. The violence of The Shrouds is understated, while the unassuming tranquility of certain scenes (an encounter by a waterfall; two characters sharing breakfast) is unexpected.

There are allusions to necrophilia, not because Cronenberg explicitly engages with the theme, but rather leaves its possibility hanging in the ether with stomach-coiling discomfort. Even AI is presented as a paranoia-fueling menace that lowers the user’s guard via pleasant, versatile avatars – despite its dehumanized status as “technology,” we neglect to address the human face that makes it hum with an unsettlingly omnipotent power.

I kept thinking of a Cronenberg quote that spoke to his treatment of cinematic death – that he took it seriously because he saw it as a rehearsal for his own demise. How ironic that, in his 82nd year, the filmmaker known for his transformative, groundbreaking innovation would latch on to a concept more nebulous, intangible, and difficult than any FX shop could practically visualize. His suggestion of watching the deceased like some sort of macabre, real-time necropolis also speaks to the life-after-death permanence of cinema, long after the creators and contributors have left the plane of human existence and assumed their own shrouds in the unknowable beyond.*

(* = Cronenberg has famously stated his atheistic viewpoint in interviews; I’m more of an agnostic)

4 out of 5 stars

Leave a comment