There were at least 3 people (myself included) at the sleepy weeknight screening of Todd Phillips’ Joker: Folie a Deux. I was down front, while the other attendees were somewhere in back. As the credits rolled, I heard a boisterous voice say: “…first 90 minutes of nonsense” followed by “…spit in the face.”

Given the one-sidedness of the conversation, I assumed he was talking to someone on the phone (I didn’t turn around to look), and it reminded me of those scenes from old movies, where the reporters in oversized coats, with notepads and a “press” tag stuck in their fedoras, rush the payphones to give their editors the latest scoop on some big criminal trial. (I like the gag in Airplane! where the row of booths keel over from the force of all the reporters rushing in.)

Which is ironic, I guess, because a big chunk of JFAD is spent in a courtroom, where Arthur Fleck (Joaquin Phoenix, as compelling as ever) is called to task for the five – but really six – people he murdered in the first film. The age-old question is: was it Arthur doing the killing, or was it his Joker persona?

While the first part of Phillips’ sequel observes Arthur in his dreary, dungeon-like Arkham Asylum digs, he’s a relatively subdued – almost marginal – character until a seemingly chance meeting with Lee Quinzel (Lady Gaga, surprisingly good) puts him on a precarious path.

A point of contention likely to rankle those firm believers in Harley Quinn’s backstory – a successful psychiatrist put under the spell of the Joker’s homicidal whims, thus making her a puppet in his diabolical schemes – is the inversion of said backstory. Here, she presents under the façade of a screwed-up arsonist with a poor home life, ingratiating herself to Arthur by proclaiming her love for a made-for-TV movie about his exploits. To be reductive – yet accurate to the film’s representation – she’s a groupie on par with the similarly “committed” Manson Girls. Lee is the live-wire presence that screams, “toxic fan – back away” – so I can see how some may be turned off by this messaging, especially if they viewed Arthur and his exploits in the original Joker as aspirational.

But appearances can be deceiving, backstories can be fabricated, and this version of Quinzel – and Gaga’s brave depiction – is ultimately contrary to what we’ve seen before. Within a lore where the character was presented as a Manic Pixie Dreamgirl with an oversized mallet, here shebecomes a manipulator of the weak and broken man Arthur really is. The tragedy of Arthur is his reluctance to admit how badly he’s getting fucked until it’s too late, hinging on hopes of “love” and “normality” that never materialize.

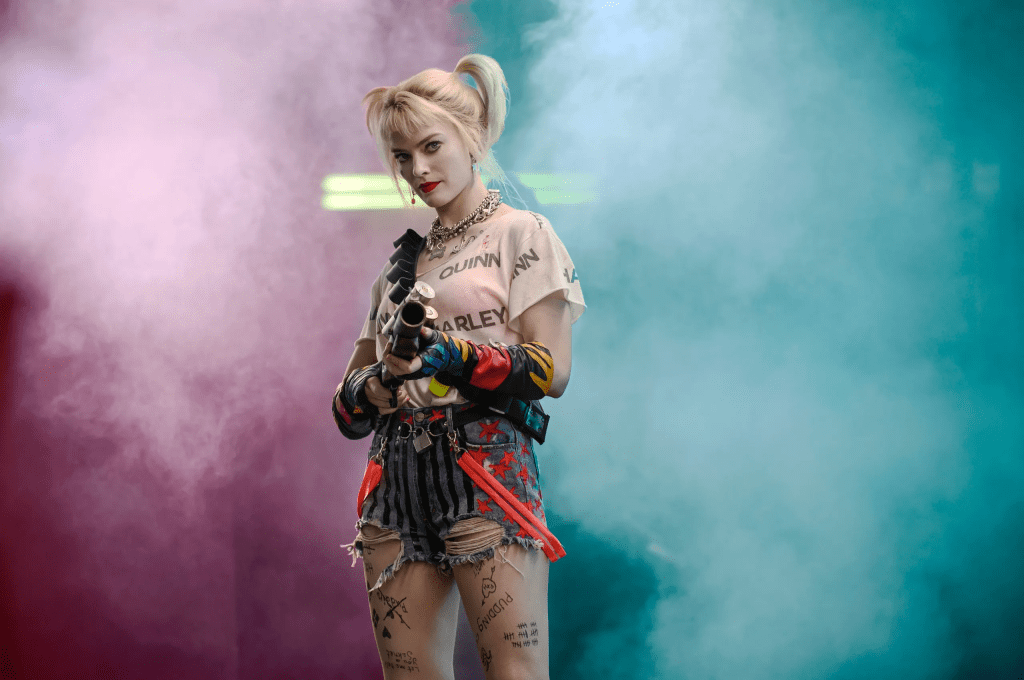

Neither Arthur nor Lee are presented as role models, and the movie makes this much clear: Arthur remains a damaged, highly flawed piece of a mutually broken mental health system, whereas Lee represents wealth and privilege – the inverse of Margot Robbie’s fun-loving, liberated-from-Joker interpretation in Birds of Prey.

The weird thing is, JFAD is neither an apologia for nor corrective to the anarchy writ large in Phillips’ 2019 effort. The latter looked to the microcosm of a dreary urban hellscape (ostensibly set in the 1970s, per the retro Warner Bros logo that kickstarts the film) to tell a tale of disenchantment, disaffection, and the insanity one encounters in a world ruled by apathy and economic disparity. JFAD, conversely, becomes a more confined effort – literally and figuratively – and serves as a mostly impartial, outsider-looking-in deconstruction of the Joker persona, Lee, and the madness scratching away inside their skulls.

Some of this is manifested through the beautifully oppressive cinematography (by Lawrence Sher), which conjures a mix of the highbrow dankness of David Fincher and the lowbrow grit of a Saw sequel (which may sound redundant, but a distinction can be made). Additionally, I like the bit of production design that presents the Alcatraz-styled Arkham as unavoidably connected to the rest of the city through the curving vein of a bridge, visually conveying that crime, violence, and mental illness are always intertwined with so-called “civil society,” no matter how much the powers that be insist otherwise.

To that end, who isn’t on a steady regimen of meds to block out the everyday nuisance of just plain existing these days?

Phillips and co-writer Scott Silver take various aesthetic and narrative detours to deconstruct Arthur and the events of Joker. JFAD is part dreary prison picture (complete with a head guard played by the ever-reliable Brendan Gleeson), part courtroom drama (with echoes of Manson’s media-circus cult of personality), and part musical…where Phoenix and Gaga detour into sequences of slickly-produced song routines that add further shading to their psyches.

These transitions into musical territory are unpredictable, and the fantastical glamorization of the imagery (found in the Harley-Joker relationship idealization) carries with it an undercurrent of sadness – a flurry of oxytocin at the Honeymoon Stage of a relationship that sees its true test of devotion once the ‘love hormone’ wears off. To a similar end, the sex scene between Arthur and Lee is quick and pathetic; a couple seconds of jackrabbit excitement that fizzles into disappointment.

Phillips has created another comic-book movie that’s really a horror show about the world right now – JFAD sticks the landing while something like Civil War flounders under the weight of its deluded sense of self-importance. It suggests that killing your darlings is an inevitable sacrifice in a world gone mad, which will make some viewers extremely unhappy…and I can’t help but admire that.

4.5 out of 5 stars

Leave a comment