For as much acclaim as it received, some reviewers trashed Todd Phillips’ Joker as irresponsible incel porn, or a glorification of vigilantism a la Death Wish or Taxi Driver. Or a reckless glamorization of mental illness. Or, when all other criticism failed, its resemblance to Martin Scorsese’s The King of Comedy.

I still view this 2019 film as a masterpiece (despite and because of the above) – a work of art that captured the pre-pandemic, pre-2020 election zeitgeist with a gritty coarseness that I found eminently relatable. While I don’t view Arthur Fleck (a masterful Joaquin Phoenix) as an aspirational – let alone heroic – figure, his cauldron of repressed rage casts the real-world devolution of civil discourse in a damning – yet truthful – light.

When Arthur tells his long-suffering case manager, “all I have are negative thoughts,” he may as well be referring to our modern addictions to social-media sites that drag intelligent conversation into the muck of sensationalism and extreme viewpoints. In these settings, the volume of all the collective noise takes priority over rationalization and coherent thought.

Perhaps you’re wondering why I’m talking Joker when it’s almost 4 years old…but it’s the movie that immediately sprang to mind while I watched Greta Gerwig’s Barbie.

Talk about your contradictions, amirite? Allow me to explain.

Phillips presented Gotham City as a gritty, 1970s-New York City-styled landscape – an inescapable hellhole where rats are becoming the dominant species. Gerwig presents Barbieland as a bright, cupcake-colored dreamscape where the perpetually positive residents – Barbie (Margot Robbie) and Ken (Ryan Gosling) and an extensive collection of other “Barbie”s and “Ken”s – couldn’t conceive of a better world if they tried.

Part of the genius of Barbie is its marketing campaign: focusing on pun-happy dialog and naïve innuendoes, the trailers gave the impression that the action would not leave the realm of product-bound fantasy. I wondered how even a director as assured as Gerwig (who co-wrote with her real-life partner, Noah Baumbach) would make this premise work as a feature film.

Well, at the end of the first act, Barbie has an existential crisis – entertaining her first-ever thoughts of mortality – and finds herself (along with Ken) making an important, fact-finding journey to the Real World to figure out what’s going on. What ensues is a series of encounters that puts her perceived status as a positive influence on society into question. Meanwhile, Ken checks out some library books, discovers the word “patriarchy,” and takes his newfound knowledge back to Barbieland.

And if Ken transforms Barbieland into a douchey haven of oversized pickup trucks, inefficient mini-fridges, and a legion of subservient Barbies, Christopher Nolan’s Oppenheimer presents a historical biopic that, by dint of its era, centers largely on the boy’s club that helped create the atomic bomb.

But perhaps the most common thread running through the zeitgeist-capturing Barbie and Oppenheimer (and Joker, for that matter) – is that of individuals on quests of self-actualization: the higher consciousness associated with the discovery of one’s true purpose; or the discovery of one’s true purpose through the invention of something that could destroy the world.

Barbie is a model of perfection who becomes afflicted by real-world maladies when her owner (America Ferrara) falls into a depressive, existential slump. J. Robert Oppenheimer (a brilliant Cillian Murphy) is a soft-spoken, repressed man torn asunder by his conflicting allegiances to science, social justice, and the moral conundrum of dedicating his intelligence and resources to a weapon of mass destruction.

In some ways, the decision to release Barbie and Oppenheimer on the same day was ingenious, as they present the masculine-feminine side of the same coin, and in turn provide distinctly contrasting cinematic experiences while still containing sneaky shared elements.

Barbie is hugely entertaining in a crowd-pleasing, no-audience-member-left-behind sort of way. But it’s also surprisingly intelligent (or maybe not so surprising, considering the skilled character studies that have distinguished Gerwig and Baumbach’s directorial efforts), incorporating a meta-narrative that impressively asks, “who is Barbie?” and approaches the “answer” from a myriad of different angles (from the literal to the more abstract). By juxtaposing the idealized Barbieland against the Real World, Gerwig and Baumbach present arguments for the fallacies of utopia, but also come to the conclusion that a happy medium is not outside the realm of possibility.

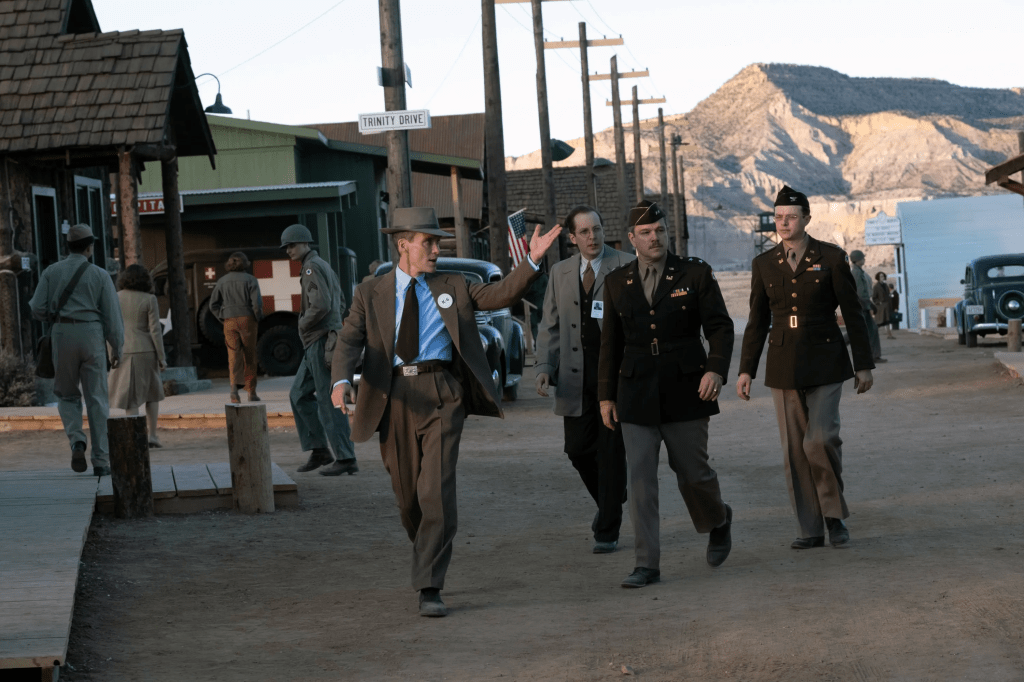

Perhaps that’s where Oppenheimer scratches a more cynical itch. While Barbie goes on a fact-finding mission to the Real World, Oppenheimer is firmly rooted in reality, but fascinated by scientific possibilities (he creates a department at his first teaching job dedicated to science that has not yet been proven, thus “existing” – for a time, anyway – in the realm of amorphous fantasy). He quickly accumulates a following of like-minded intellectuals working to an end goal at a Los Alamos test site (which correlates a built-from-the-ground-up military science base to the perpetually sunny artificiality Barbieland; each locale founded, at least in part, by the power of its creators’ imaginations).

While Ken is presented as a himbo, he is no more nor less naïve than Barbie, who balks at the development of flat feet and cellulite. The only one who understands what’s going on is Crazy Barbie (perpetual MVP Kate McKinnon), who lives in her own cubist bungalow on the outskirts of Barbieland. Meanwhile, Oppenheimer’s heir apparent and constant confidant is Albert Einstein (Tom Conti), who pops up at several points to offer sage advice to his ambitious pupil.

Both films subsist on conundrums – for Barbie, it’s the reconciliation of an expansive palette of human emotions that infiltrate a world previously predicated on plastic ideals of beauty, community, and harmony. How does one deal with the coming-of-age realization that there’s a whole world outside of our own interests? In Oppenheimer, a world suffering the deep scars of war and man’s inhumanity presents the atomic bomb as existing within a timeline that may or may not ultimately need it.

Indeed, when Oppenheimer is invited to the White House and given private audience with Harry Truman (Gary Oldman!), who balks at the scientist’s moral reservations about dropping the bomb, the President says, in no small terms, that “no one will think of the man who created it…they’ll think of the man who dropped it.” And, in a sense, Truman is also saying to the viewer of Oppenheimer, 78 years on, that it ultimately doesn’t matter what you think about the bombing, because it happened, irrevocably changing the world – and the trajectory of weapons of war – in the process. The notion of “what could be” becomes null and void when it moves out of the realm of the hypothetical and is actualized in the most explicit manner possible.

Contrary to the pathetic online backlash by attention-seeking man-babies, Barbie isn’t a misandrist screed, but an affirmation across the gender spectrum that it is only through trial and error, individual journeys of self-discovery, and acknowledgment of one’s mistakes, that two sides can come to a consensus on “the way things should be.” Instead of opening in a flawed world that settles on some semblance of Hollywood “perfection” by the time the credits roll, Barbie begins in an artificial concept of perfection, works its way through character-driven conflict, and comes out the other side in a world that trades perfection for a sense of equality, which is perhaps why – through all the sharp humor and clever satire – the world that Barbie ends in seems more plausible than the one it started in.

Meanwhile, Oppenheimer’s “man’s world” is buffered by two key female performances, though each only takes up a small fraction of screen time: Robert’s erstwhile lover – and U.S. Communist Party member – Jean Tatlock (Florence Pugh); and his alcoholic wife Kitty (Emily Blunt). While Pugh and Blunt both stand out by default amid a perpetually shifting sea of similar-looking men in earth-toned attire, their limited autonomy is indicative of the era. That said, Blunt has a great scene where she effortlessly takes down a room of hostile lawyers, manipulating their perception of her as skittish, sensitive, and unintelligent. And, in a moment near the very end, her reluctance to shake someone’s hand – accompanied by a contemptuous look – speaks volumes.

What’s interesting about Oppenheimer as a character is, as depicted by Nolan and Murphy, he is exceedingly remote in terms of his emotional connections to humanity. That is not to say he’s an unfeeling creature, but his feelings are pressed beneath the weight of expectation that accompanies his scientific mind. He’s a tangle of paradoxes – emotional, existential, cultural, and political – whose ultimate “value” is determined by a questionable creation. In Barbie, the characters are straightforward until they become a tangle of paradoxes when they step outside their insular bubble.

Rating for Barbie and Oppenheimer: 4 out of 5 stars

(Header image by Thomas Levinson via The Daily Beast)

Leave a comment